A × B × C = OCD: Understanding OCD, Part 1

This blog post is educational and is not medical advice. Any decisions regarding beginning, stopping, or changing medications should be made in consultation with a qualified prescribing professional, such as a psychiatrist or primary care provider. So, please be sure you consult with your prescribing professional before making any changes to your medication use!

If you live with OCD—or love someone who does—you’ve probably asked yourself some version of these questions:

Why does my mind do this?

Why do I find these thoughts, these themes, so upsetting? Why these in particular?

What do these thoughts say about me? Do they mean I am bad, crazy, or dangerous?

Why am I afraid of outcomes I rationally know are unlikely to happen?

Why do I feel compelled to do things I rationally know are unnecessary?

The catastrophic outcomes I fear never happen—so why am I still afraid? Why haven’t I gotten over this already?

To answer these questions properly, we need a theory that explains the nature of OCD. That theory should be grounded in the best available scientific research, simple enough for both clients and clinicians to use, and clear about what helps—and what doesn’t—when it comes to overcoming OCD.

Without such a framework, both clients and clinicians are left in the dark, experimenting haphazardly and hoping something will work. Uninformed therapists may try a grab bag of techniques—slow breathing, positive thinking, mindfulness, tapping, finger wagging—without understanding the psychological processes they’re actually trying to change. Doctors may prescribe psychiatric medications in the hope of fixing a presumed malfunctioning brain (a reminder: your brain is not broken and, on average, adding medications to ERP doesn’t improve treatment outcomes; William and I have both spent years publishing peer-reviewed articles elaborating on this point), while overlooking the psychological processes that keep OCD going.

A x B x C Model

Although it may feel reassuring at first, an OCD diagnosis by itself cannot answer the essential questions above. A diagnosis is simply a descriptive label. It tells us that someone experiences obsessions and compulsions that cause distress and interfere with daily life. It does not explain why these experiences arise or why they persist over time. For that, we need a proper explanation—a theory that helps us understand both the problem and the path forward.

In this post, I introduce a simple theoretical framework for understanding OCD, which I call the A × B × C model. This model is straightforward, supported by strong scientific research, and useful for guiding assessment and exposure and response prevention (ERP) treatment.

Let’s walk through it together.

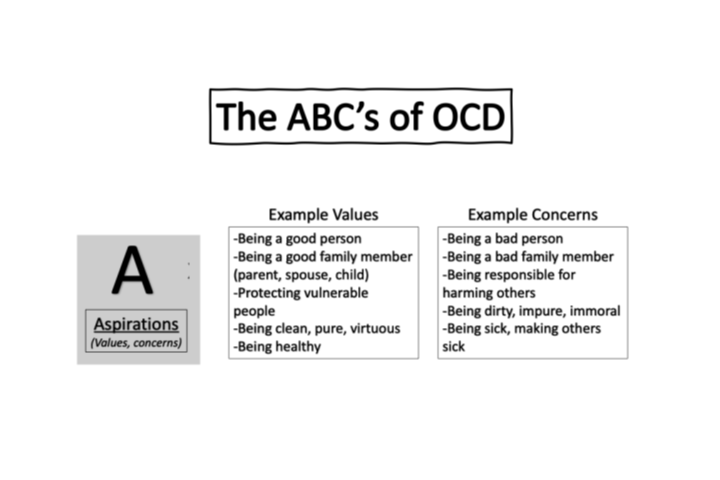

A Is for Aspirations (Values and Concerns)

The “A” in the ABC model stands for Aspirations—your values, your deepest concerns, and the things that matter most to you. These might include:

Being a good person

Being a loving parent, partner, or child

Protecting vulnerable people

Being in control of thoughts and feelings

Being clean, moral, or virtuous

Being healthy and keeping others safe

Our aspirations naturally give rise to concerns. What if I’m not a good person? What if I’m a bad parent? What if I harm my child—by accident, or even worse, on purpose? What if I’m responsible for causing harm to someone else? Aspirations and concerns are two sides of the same coin. One side reflects what we value most; the other reflects our fear of violating those values.

Aspirations are good. Caring about being moral, loving, and safe is admirable. Importantly, the “A” is the one part of the A × B × C model that is not the problem. You should be proud of your A. It isn’t what needs fixing.

At the same time, your aspirations set the stage for OCD by making you especially vulnerable to certain kinds of intrusive thoughts. Here’s a crucial point that often gets missed:

OCD doesn’t attack what you don’t value. It targets what you care about most.

OCD Thoughts Mirror Our Deepest Values

That’s why OCD thoughts feel so personal and so disturbing. The mind pulls material directly from your value system. You may be able to shrug off a thought about being struck by lightning (which is unlikely but possible) but feel consumed by a thought about harming a loved one. The difference lies in what matters most to you. The worst imagined outcomes are the ones that violate our deepest values.

OCD-related concerns are not random. They are not the result of a meaningless “brain hiccup.” They are deeply meaningful. A useful question to ask yourself is: What would I have to value for this thought to upset me so much? Often, what you’ll find is fear of violating a core value.

Aspirations are also intensely personal. One person’s values and concerns may seem baffling to someone else. For example, one mother may be consumed by fears about radon contamination in her home slowly killing her husband and children, while another person feels no concern about environmental toxins at all. That same person, however, might be tormented by fears about their sexual orientation despite being happily married and confident in who they are—something the first mother finds hard to understand. This isn’t a flaw; it’s simply how psychology works. What upsets us is shaped by what we value and what we feel responsible for.

Where do aspirations come from? They are both learned and created. Our environment, culture, and experiences strongly shape what we care about and what we fear. We learn to worry about potential dangers through our own experiences, by observing others, and by consuming information—news stories, social media, and the internet. At the same time, our creative minds generate concerns through “what if” thinking (for example, “What if the next time I feel anxious, I never calm down again?”).

In my next post (Part 2), I’ll continue walking through the A × B × C model and focus on how the mind generates intrusive thoughts—and how we respond to them.

For now, here are the key takeaways from this post:

We all have aspirations—a mix of values and concerns—shaped by our environment and our minds.

Your aspirations determine which intrusive thoughts upset you and which ones don’t.

OCD-related concerns are not arbitrary. OCD attacks your most cherished aspirations. In this sense, your obsessions reveal what you value most.